In small pockets of the intellectual heterodoxy there are rising calls for deracialization—separating race and racialization from our minds and public lives. Most certainly a minority position, this radical idea faces an uphill battle, not the least because many academics and public intellectuals take the existence of race as a social and historical fact as a basis for incredulity about the prospect of disentangling ourselves from race.

Linguist and Columbia University professor John McWhorter has said that it is beyond his capacity to wage such a battle. Glenn Loury, professor of economics at Brown and host of The Glenn Show podcast has recently featured guests who have discussed variations of this idea, such as economist Rajiv Sethi of Barnard College and the Santa Fe Institute, and Reihan Salam, president of the Manhattan Institute. After hearing these conversations, Professor Loury’s friend Clifton Roscoe felt compelled to write an essay addressing deracialization, which Glenn published on his Substack platform in August 2022. It’s titled “Race Is a Reality in America. Here’s How We Deal With It.”

No offense to those who think we should deracialize America, but that train left the station long ago. We can’t deracialize America any more than we can eradicate Covid. The best we can do is to learn to live with both.

I emphatically disagree. Here’s why.

In his intro to Roscoe’s essay, Loury agrees with those who counter the tendency of some progressives to overemphasize race, sniffing out racial bias everywhere, when we should be striving, Loury argues, for meritocracy. But giving up race altogether is a bridge too far, he contends, because “I draw sustenance from traditions particular to my African American heritage, and I wouldn’t give those traditions up for anything. Given that race will likely remain a social fact for the foreseeable future, what part should it play in our society?”

I’m also nourished by those traditions in Afro-American life and history deriving from a rich cultural heritage—spiritual, linguistic, culinary, dance, and music, for instance. Nevertheless, I’ve embraced what Dr. Carlos Hoyt, in The Arc of a Bad Idea: Understanding and Transcending Race, calls a “non-racial identity.” Is it possible to separate race and heritage, race and culture? Yes.

Separating Race and Culture

For sure, it’s certainly true that many of the cultural responses that we Black Americans, as a self-identifying group of people, have made were directly as well as indirectly related to the American racial predicament. However, that history does not mean that we can’t or shouldn’t appreciate and embrace those cultural riches without holding on to the concept of race—and the practice of racialization.

I’m far from the first to make a distinction between race and culture. The late writer and cultural critic Stanley Crouch wrote in 1994: “We can no longer afford to traffic in simple-minded and culturally inaccurate [emphasis added] terms like ‘black’ and ‘white’ if they are meant to tell us anything more than loose descriptions of skin tone. We are the results of every human possibility that has touched us, no matter its point of origin.”

Also in 1994, author and cultural philosopher Albert Murray was interviewed by a fellow novelist, Louis Edwards. Murray made a clear differentiation: “. . . if you go from culture, instead of the impossibility of race . . . You see, race is an ideological concept. It has to do with manipulating people, and with power, and with controlling people in a certain way. It has no reality, no basis in reality. . . So what you enter into to make sense of things are patterns and variations in culture. What you find are variations we can call idiomatic—idiomatic variations. People do the same things, have the same basic human impulses, but they come out differently.”

Ralph Ellison, author of the classic novel Invisible Man, published 70 years ago, was interviewed by three Afro-American writers, Ishmael Reed, Steve Cannon, and Quincy Troupe, in 1977. Ellison: “. . . the pervasive operation of the principle of race (or racism) in American society leads many non-Blacks to confuse culture with race [emphasis added] and thresholds with steeples, and prevents them from recognizing to what extent the American culture is Afro-American. This can be denied, but it can’t be undone since the culture has had our input since before nationhood. It’s up to us to contribute to the broader recognition of this pluralistic fact. While others worry about racial superiority, let us be concerned with the quality of culture.”

Of course, confusing race and culture occurs among nominally black folk also.

I spent a considerable portion of my 2020 course, “Cultural Intelligence: Transcending Race, Embracing Cosmos,” bracketing and distinguishing between race and culture based on insights such as those above. From my perspective, race is a categorization and hierarchical sorting of human beings into subspecies based on skin color and phenotypic differences. The express purpose of such selecting and sorting—and, as we shall soon see, of attribution, essentializing, and acting in a racist manner—was to enable the oppression and exploitation of darker-skinned people into a caste-like structure whereby those classified as white had more ready access to the social, economic, and political benefits and opportunities of a modern system of free enterprise.

Culture, rather, is human meaning and values expressed in forms of creative production (art and technology), rituals, patterns of behavior, and ways of seeing and being in the world—lifestyles. One can also view culture as shared agreements, practices, and symbolic communication among groups of people. Another approach to culture is more developmental, as in the use of education to cultivate and improve human capacity to elevate and refine—becoming more “cultured” thereby.

In How Culture Works, anthropologist Paul Bohannan used a simile to describe how culture helps humans expand beyond our biological inheritance.

Culture is like a prosthesis—it allows the creature to extend its capacities and to do things that its specialized body cannot otherwise do.

By definition and intent, race separates and divides. Conflating race and culture twists and tightens this division. Separating or bracketing culture from race tends toward appreciating human commonalities and differences in a more mature manner than judging and stereotyping groups of people based on skin color will allow.

Scales of Deracialization: Separating Race from the State

Another reason I disagree with Professor Loury and Mr. Roscoe is because of their presumed scale of deracialization: the entire society. As Roscoe says, “we can’t deracialize America.” Why not? Here’s his claim:

Perhaps the best argument for why we can’t deracialize America is that activists won’t allow it. They use race as both an offensive weapon (“Everything about America is racist, and so are you if you don’t agree!”) and a defensive weapon (“You’re not black, so shut up and listen to us!”). They even use race as a weapon against black people who disagree with them (“You’re not ‘authentically’ black, so you shut up, too!”).

Seems to me that the self-serving, spiderweb logic based on race that Roscoe objects to would be even more of a reason to pursue deracialization. One approach toward this end would be a separation of the state and race, as David E. Bernstein argues in his recently published book, Classified: The Untold Story of Racial Classification in America.

Disaggregating race from the state can begin through the U.S. Census, which currently compels people to racialize themselves by asking: “What is this person’s race?” Carlos Hoyt recommends adding this question: “How is this person racialized?” By making note of how others racialize us, the government could still track bias, discrimination, and differential outcomes based, at least partly, on how one is racialized. Furthermore, those who don’t identify by race at all could check a box. And those who wish to continue racializing themselves can do so too. The 2030 Decennial Census Form, then, could look like this:

This page was created by Carlos Hoyt as part of a petition to abolish compelled self-racialization in the U.S. Census

Deracializing Oneself and Others

Moreover, the scale of deracialization could be smaller. An individual can choose to stop racializing his or herself, and to stop racializing others in speech, thought, and behavior. The same is true for smaller groups of persons rather than an entire society of 335 million people.

There are notable individuals who have consciously and deliberately stopped identifying with the concept of race and who abjure the process of racialization. Author Thomas Chatterton Williams believes that it is possible and crucial to “unlearn race.” Jewish American executive coach Amiel Handelsman has embraced the goal of deracialization. Dr. Sheena Mason advocates a pro-human stance that she terms “racelessness.” Likewise, Dr. Hoyt advocates “anti-racialization.” In fact, Mason and Hoyt and I co-facilitated a conference in September 2022, “Resolving the Race-ism Dilemma,” grounded in this very perspective.

Artist and National Book Award-winner Charles Johnson argues that whereas we certainly shouldn’t be blind to the ways we have been racialized historically, neither should we be bound to it either. The Fifth Column podcast co-host Kmele Foster, a staunch libertarian individualist, calls himself a “race abolitionist,” and goes as far as rejecting self-identification as “black,” presumably because of the racial connotations of the word. Writer and co-host of the FAIR Perspectives podcast, Angel Eduardo, disavows race and racialization. Marine and educator Carlen Charleston, based in Texas, founded a nonprofit in 2018, ERASE Races, dedicated to ridding the nation of the concept of race while unifying across all ethnic boundaries through good works. Financial advisor and wealth consultant Adrian Lyles, based in Calhoun, GA, has created a nonprofit, P.U.L.L.—People United in Life & Liberty, where, on their website, they declare:

We seek to educate that how we define race is not only antiquated, it is widely obscure. No one can define what it means to be black or white. We believe there is one race of people called “Human.”

Are all of the people above simply deluded? Are they in denial about the history and even the continued prevalence of racism in the United States? Are they obtuse, blind advocates of color-blindness in some wish for a “kumbaya” future without conflict?

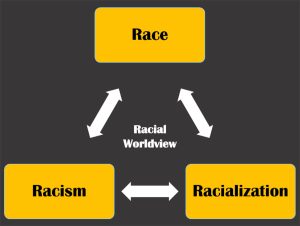

No. Each of these individuals has undergone deep self-reflection and study. Even though differences of emphasis can be found among them, they have concluded that the concept of race is fatally flawed. I emphatically agree. Further, the concept of race is kept alive by its prevalence in mainstream and social media, by the process of racialization, and by a ruinous ideology called a “racial worldview.” The late anthropologist Audrey Smedley, author of Race in North America: The Origin and Evolution of a Worldview, once described a racial worldview this way:

By racial worldview, I simply mean believing and acting in accordance with the social convention that people can and should be regarded as members of one or more of a handful of nebulous, restrictive, contradictory, and conflicting subspecies called races.

Here’s how this noxious feedback loop works:

Yet to deracialize at any level—individual, interpersonal, or institutional—one must know what racialization is. It is not sufficient to assume that because race as a concept exists as a social norm and social fact that one, per se, understands racialization.

What Is Racialization? Is it Inevitable?

Racialization is the process or system by which races are made:

Let’s take each step in the racialization process one-by-one and ask ourselves if it would be possible to stop.

- Would it be possible to stop selecting human characteristics such as skin color, hair texture, the size and shape of one’s nose and lips, and ancestral origins as signs of so-called “meaningful racial” difference? Indeed, modern science has determined that the biological conception of race is false, and that even diseases shared by members of ancestral groups from particular regions—for example, sickle cell anemia, which developed among descendants who lived in malarial regions across the Mediterranean and Central and West Africa—are not exclusive to a “racial” group. According to the 2003 documentary, Race: The Power of an Illusion, in parts of Greece, 30% of the population carries the sickle cell trait. The differences among human populations should not be determined by a crude measure like “race.”

- Would it be possible to stop sorting human populations into uniform sub-populations based on those selected human characteristics? If throughout the span of recorded history, human beings had always sorted based on external physical characteristics and ancestry, then a strong case could be made that this is simply the way humans classify one another. However, although the cognitive practice of categorization is common among humans, the racialization chart above makes clear that the practice was codified in the United States in the 1700s. Racialization is not an eternal aspect of the human condition. If we began at a particular point in history to sort human beings in this way, we can creatively exercise human cultural intelligence and agency to choose otherwise.

- Would it be possible to stop attributing traits (temperaments, talents, behaviors) to racial types? If we understand why and how human beings stereotype others into fixed and oversimplified images, we can grow beyond such a practice. Those drawn to white nationalism, for example, view non-white peoples as a threat based on stereotypes and a psychological need to bolster their self-concept by feeling superior to those perceived “others.” If blues musician and social activist Daryl Davis could, through empathy, deep listening, music, and heartfelt logic, convince a number of KKK members to come out of their robes and disavow racism, then on a larger scale we can grow beyond stereotyping individuals into racial subspecies who supposedly think and behave the same because of select human characteristics as skin color. Doesn’t the idea that we can tell important things about a person’s values, skills, and experience solely based on their external features strike you as absurd?

- Would it be possible, in turn, to stop viewing differences based on the illusory idea of race as natural, immutable, and hereditary? If 1-3 are possible, and they are, then not essentializing human beings based on race is not only possible but desirable. In fact, this heightened consciousness beyond essentialism has already been accomplished by millions of people since the advent of the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s.

- Is it possible to not be racist, to not believe in race and treat people by a double standard based on their racial classification? Indeed, it’s possible and millions have decided, from the 1960s to today, that being an overt racist is socially unacceptable, beyond, so to speak, the pale of the Overton window. Of course, there are still people who hold racist beliefs and enact racist behaviors. Researcher Seth Stephens-Davodowitz, author of Big Lies: Big Data, New Data, and What the Internet Can Tell Us About Who We Really Are, uncovered evidence of explicit racial hatred through Google searches. The racial epithet, in either singular or plural form, included in seven million American searches every year is “nigger”—often as searches for “nigger jokes.” Nevertheless, in our legal system and in our public discourse, a belief in racial reasoning and justifications for it—up to and including Affirmative Action and “anti-racist” calls for “equity”—are being called into question by a rising tide of persons whose values align with classic liberalism.

Conclusion

If we value the dignity of each and every individual, and if we believe that we share equal citizenship status as Americans based on that dignity, those principles are a good start for the deracialization effort. Let’s share the value of deracialization with individual American citizens and let them decide whether to continue racializing themselves and others or to stop this lethal practice in their own minds and behavior.

Deracialization can be achieved while maintaining allegiance to specific idioms and practices that derive from cultural, ethnic, religious, and ancestral identifications. I know this is true because I myself have enacted this perspective by remaining rooted in an Afro-American cultural milieu via my family, close friends and associates as well as the blues, jazz, gospel and other forms and artifacts of expression by my idiomatic group. Yet I’m also a citizen of the wider world, as cosmopolitan as jazz itself has become. I’m willing to venture that there are many others in the U.S. and elsewhere who would take to heart a stance of “rooted cosmopolitanism” without maintaining a belief in the idea of race, the practice of racialization, and a calamitous racial worldview—if they were given the choice.

If we stop conflating race and biology, race and culture, race and heritage, race and ethnicity, race and ancestry, even race and economic and social status, we can disentangle ourselves from this gordian knot of racialization and move closer to the fulfillment of our democratic American creed. I agree with the master novelist and essayist Toni Morrison, whose writings wrestled with ways to acknowledge the impact of race and racialization without being bound to it, whose writings are a testament to the humanity of ancestors too often forced to be fugitives in their own land, whose writings sculpted and shaped a way to recognize a cultural home for the many thousands gone whom others were intent on making existentially homeless through bigotry and the folklore of white supremacy. In a 1994 essay, “A Race in Mind: The Press in Deed,” Morrison wrote these wise words:

. . . although historical, race bias is not absolute, inevitable, or immutable. It has a beginning, a life, a history in scholarship, and it can have an end.

Deracialization won’t be easy. Neither was sending astronauts in rocket ships to the moon, ending the transatlantic slave trade, ceasing to believe in witches or that the universe revolves around the earth. A long, hard road ahead doesn’t mean that we should give up, lacking the guts and courage to scaffold deracialization over time. If we do so, perhaps we can move closer to an Omni-American variation on the nation’s motto, E pluribus unum: Out of many, we embrace a common pluralism of civic excellence and cultural accord.

Fantastic piece! I’m 100% in agreement. Thanks for posting.

Greg, I have always valued your work. But I’m still not clear on why #1&2 in your list are necessary for #3-5. Couldn’t it just as well be the other way around, that #3-5 need to happen before #1&2?

Hi Teri,

You very well may be correct! I simply followed the order of racialization in the chart, but as long as we get to all of them, I’m agnostic as to the order.

Best,

Greg

Great article. Identification of race on census forms has to go. This is the primary source of structural racism in the U.S. today. We have to start treating everyone as equal as the equal rights legislation intended. As soon as you identify people by groups and do statistical analysis on these groups, you can treat them differently and make groups, not individuals as sovereigns. I was in the army with a mixed-racial unit, and when you work side-by-side on a mission, you don’t think about racial differences. Get the government out of playing race cards and we’ll do much better.

This is a thoughtful article, but doesn’t account for the incentives that racially similar people may have for using shared racial attributes as an organizing construct. Organizing around race can be a source of social and political power, and perhaps many feel that this is is the only way to amass sufficient power to fix problems that are historically grounded in — or correlate highly with — race. To these individuals and groups, a call to “deracialize” might sound instead like an asymmetrical call to disarm in the face of many remaining uphill battles for improved economic, social, and political outcomes.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts, Kristin. Considering how the racial construct of “whiteness” has been used for several hundred years as a source of social and political power, certainly what you say is true. You of course mean it when others racialized as non-white use it to counter problems associated with race, but hopefully my opening sentence above points to how this leads to a never-ending, zero-sum conflict of using “race” to gain power.

Perhaps you and the others you allude to assume that “deracialization” implies “de-politicization.” This assumption is not the case, which is why the Census proposal allows people to make clear how they are racialized in order to continue tracking discrimination correlated with race. It also allows people who want to continue self-racializing to do so.

Further, a slight shift in language will allow for the organizing that I agree is important, without reifying the fallacious concept of race and a racial worldview that keeps it alive. If people who have been “racialized as black,” for instance, need to organize based on a shared “status of racialization,”–not “shared racial attributes”–then that is how I suggest saying it. This is not mere semantics, as the way we use language both reflects and influences reality.

I’m looking for a way to get off the treadmill of racialization, not stop persons who have been racialized from organizing politically.

Thank you for elucidating these ideas. Im Canadian, but we have been importing American ideas about race, CRT ect, In our project of reconciliation with indigenous people. Along the way, I feel we are re radicalizing thought through the use of language. “Bipoc” and “indigenous” and “whites” or “colonizer/settlers”. Where racialized language had been receding throughout my lifetime, It is now commonplace in my cultural milieu to refer to these groups as realities. Oppressor vs oppressed. I see what you see in terms of the circle which leads to more racism. I appreciate your perspective and have tried having conversations which call into question our present tactics for achieving reconciliation only to be yelled at. Im told this a time for listening. As a colonizer, “Ive had my time” they have said. Im not sure what to do but I see this going in a bad direction. Each skin tone group hiving off into their own world view seems antithetical to what always inspired me. Mutual respect has been put aside. A racial reckoning is what people seem to crave in my progressive circle. To question is to be outed as …….guess what, a racist colonizer. I appreciate your words.

Hi Jon,

I so wish you could have taken the six-month course that I co-facilitated with my colleague Amiel Handelsman and my partner, Jewel Kinch-Thomas, “Stepping Up: Wrestling with America’s Past, Reimagining its Future, Healing Together.” You may find the free eBook that we created for the course to be helpful: https://www.steppingupjourney.com/reimagining-american-identity/.

It’s sad that a group we call “postmodern progressives” are blind to their own shadows and the inevitable blowback from their self-righteous, dismissive, and reductive tactics and approaches to the so-called racial reckoning. Since you’re in Canada, you may find this essay by Aftab Erfan, the Chief Equity Officer of the city of Vancouver, to be useful: https://integral-review.org/pdf-template-issue.php?pdfName=vol_17_no_1_erfan_the_many_face_of_jedi.pdf.

Don’t give up. And don’t buy into the essentialist nonsense that simply because of the color of your skin, you are automatically a “racist colonizer.” Let me know what you think of the content I’ve shared with you. Be well and thanks for commenting.

Thank you for this great article. I couldn’t agree more. I have often struggled to put to words my thoughts on this very subject in a way that others can possibly understand. I appreciate having this as a reference to share with others to set the table for further discussion.

And thanks for your comment, Richard.

I like your differentiating race from culture. We all have ethnic heritages – mine is Irish and Alsatian on my mom’s side, German and English on my Dad’s. And celebrating our family histories, no matter where we’re from, can be both fulfilling and fun.

BUT … I’m not defined by those. And even the wokester racialists wouldn’t demand I be defined by those. But they do demand that those whose families hail from African, Asia or Spain be so defined.

The whole “racial identity” world view is itself based on a double standard – one that, curiously, holds non-Caucausians to a different standard.

Well, that’s how the race-racialization-racism nexus, grounded in a racial worldview, works: double standards galore. Since for centuries, the double standard was used to dominate persons racialized as black, perhaps it was inevitable that at some point that would boomerang back the other way. Fortunately, those you call the wokesters aren’t literally lynching people, as happened for far too long in our country. But the way cancel culture is used, with social media as an accelerant, is awful. Some wiser voices on the left are promoting a call-in culture over a call-out one. My approach would defang the very concept of race and related forces, so the double standard would go away eventually. But realistically, in-group/out-group dynamics, status, ethnocentrism, and bigotry based on fear of the other will likely be with us in some form or another for some time to come. But it doesn’t have to be based on a fictitious identity such as race.

Jim Trageser’s comment above: “The whole “racial identity” world view is itself based on a double standard – one that, curiously, holds non-Caucausians to a different standard” is the essential point, often forgotten.

Back in eary 70’s at the City University of New York (CUNY), I taught Literature of the Non-Western World, the term I disliked but was required to use for the college text book Harper Collins commissioned me to create. Anyway, my approach was to honor racial, physical and cultural differences as natural and a matter of celebration. I called my stance the “Pedagogy of Awareness” capsualized in my copyrighted phrase: “Let’s celbrate our differences, so we can enjoy our oneness.”

Racila differences — as well as all others — caucasian and non, must be celebrated fro their nuances.

A key point of my essay is the fundamental fallacy of the concept of race, based on a bogus process of racialization, and a spurious racial worldview. Yes, there are differences in ancestries, ethnicity, histories, and traditions among people. But if I were to say “racial differences must be celebrated for their nuances,” that would belie a belief in the validity of race as a category of dividing human beings into subspecies. I don’t believe that there are subspecies of humans similar to dogs being a subspecies of wolves. There’s a human race, yes, but not human “races”. That’s a nuance I can get with.

Thank you Greg. Your article exemplifies a third tier Integral perspective, articulated clearly and with love. You make important distinctions that are obvious once they are named.

I have been trying to articulate my view that many of us trying to come to terms with our own biased behaviors are at various points along the spectrum of development of our ability to include others. As such, we have made mistakes and have made unpopular stands as well. But I keep finding myself categorized on one side of the binary racist vs. anti-racist classification because I do not parrot the correct jargon. I am a work in progress, but I’ve found that “conversing” with anti-racists is not conducive to learning and growth. Your article helps me understand myself better, helps me calm down, and gives me expanded vocabulary to explore my own path to growth.

Excellent Article, Excellent Blog , Excellent Site ✅✅✅